The evolution of manufacturing technologies has given rise to two dominant approaches: additive manufacturing (AM) and subtractive manufacturing. While both aim to produce functional components, their methodologies, capabilities, and limitations diverge significantly.

Subtractive manufacturing achieves precision through material removal. It starts with solid material billets (such as metal ingots and plastic slabs) and uses techniques like Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining, milling, and lathing to systematically remove material and obtain the desired geometry. This process boasts distinct advantages: it delivers excellent surface finish and high dimensional accuracy (with a tolerance of ±0.025 mm), the load-bearing surfaces feature superior mechanical properties due to the isotropic grain structure, and the mature technology has been widely adopted across industries. However, it also has obvious limitations: material waste is substantial (the scrap rate can reach up to 90% for complex titanium alloy parts), it is constrained by geometric shapes (e.g., internal channels and lattice structures are usually unachievable), and tool wear accelerates when processing hard materials like titanium, increasing production costs.

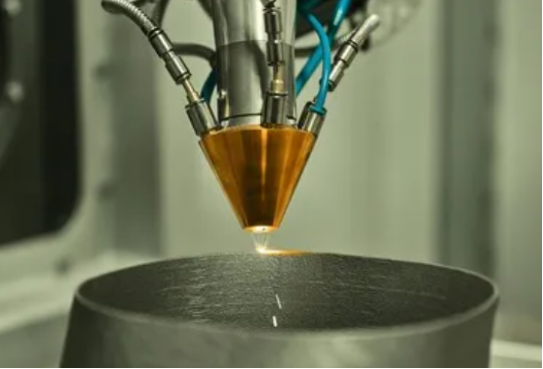

Additive manufacturing builds parts through layer-by-layer deposition. Based on digital models, it forms components by depositing materials (typically metal powder or polymer) layer by layer, with key technologies including Selective Laser Melting (SLM), Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), and Binder Jetting (BJ). Its core strengths lie in: near-net-shape production that minimizes material waste (with a scrap rate of less than 5%), unparalleled design freedom (enabling the manufacturing of organic shapes, internal cavities, and lightweight lattice structures), and the ability to achieve rapid prototyping and customized production (such as patient-specific medical implants). Nevertheless, it has shortcomings: the surface roughness is relatively high, often requiring post-processing; anisotropic material properties may affect structural integrity; the build volume is limited, and the production speed is slow for mass production.

Material efficiency is a critical dividing line between the two, especially evident in the processing of high-value metals. Traditional titanium alloy machining wastes a large amount of raw materials, while additive manufacturing utilizes over 95% of the input powder. This efficiency aligns with sustainability goals and can reduce raw material costs in the long run.

In terms of the trade-off between design flexibility and precision, additive manufacturing excels in applications requiring complex structures: in the aerospace field, it can produce topology-optimized brackets that reduce weight without sacrificing strength; in the medical field, it enables the production of porous bone implants that promote tissue integration. Subtractive manufacturing, on the other hand, dominates scenarios with rigid precision requirements: such as engine components needing micron-level tolerances, and optical or sealing surfaces requiring mirror finishes.

Hybrid manufacturing solutions are emerging as a trend to integrate the strengths of both. Forward-thinking manufacturers are increasingly combining the two processes: using additive manufacturing to produce near-net-shape parts with complex features, and then employing subtractive machining to refine critical surfaces and interfaces. This synergistic model balances innovation and reliability, such as turbine blades with 3D-printed cooling channels and CNC-finished airfoils.

In terms of sustainability considerations, additive manufacturing supports a circular economy, where recycled powders (such as titanium alloy scrap) can be reused in closed-loop systems; while the recycling rate of subtractive manufacturing is improving, it still faces challenges in segregating metal chips and restoring material properties.

Regarding the future development trajectory, with the advancement of digital manufacturing technologies, the choice between additive and subtractive processes will depend on three core factors: part complexity (the trade-off between geometric freedom and structural simplicity), production volume requirements (the difference between mass production and customized batches), and sustainability mandates (material efficiency and carbon footprint indicators). Hybrid solutions are likely to dominate high-value sectors, while specific application scenarios will lean toward a single process. The era of "either/or" is coming to an end, and industrial success now lies in the strategic integration of the two processes.